دسترسی بیشتر

سواد دوره محمدرضاشاه

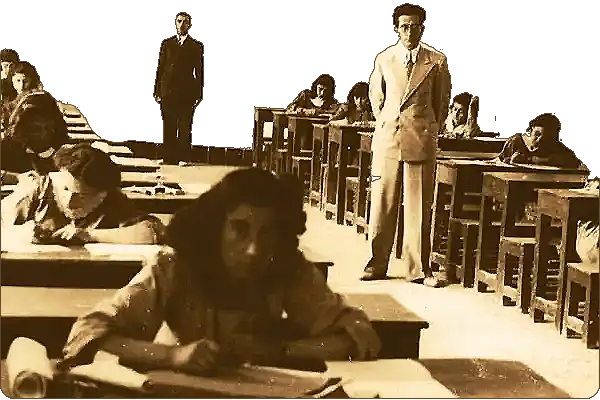

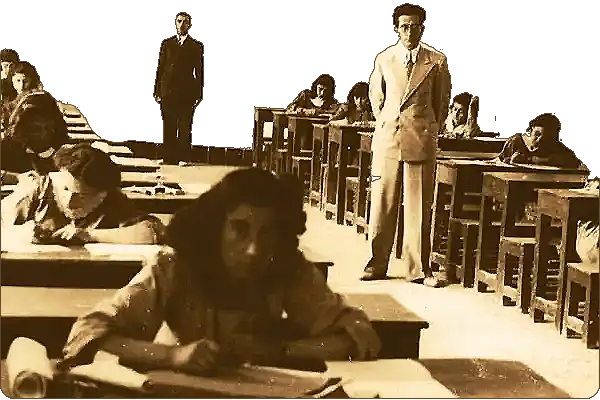

سیستم آموزشی کشور

محمدعلی [همایون] کاتوزیان، عضو دانشکده مطالعات شرقی دانشگاه آکسفورد، در کتاب «اقتصاد سیاسی ایران مدرن: استبداد و شبه مدرنیسم» مینویسد:

سطح آموزش پایین آمد و فارغالتحصیلان مؤسسات آموزشی حتی از اخلاف خود نیز بیسوادتر بار آمدند. تمام اینها سوای مشکلاتی است که مسئله همیشگی تمرکز زیاده از حد بوروکراسی پیش میآورد و وزارت آموزش و پرورش و وزارت علوم را در تهران به نحو عجیبی درگیر مشکلات آموزشی نقاط دور دست کرده است؛ ساواک بر کارکنان دانشگاهها فشار وارد میکرد تا در امور اداری و آموزشی با دانشجویان مدارا کنند، به امید آنکه نارضایتی سیاسی گسترش نیابد. بر طبق یک نمونهگیری از وزارت علوم که در ژوئن 1973م [خرداد ۱۳۵۲ شمسی] منتشر شد، ۴۸ درصد از دانشجویان دانشگاهها (که جواب داده بودند) از خانوادههای بوروکرات، ۳۵ درصد از خانوادههای بازاری و صاحبان صنایع، ۷ درصد از خانواده مالکان و کشاورزان صاحب زمین، ۲ درصد از طبقه کارگر شهری و ۱ درصد از روستاییان بودند. یادآوری این نکته مفید است که در سال 1973م [خرداد ۱۳۵۲ شمسی] دو طبقه آخر (کارگران شهری و روستاییان) حدود ۸۵ درصد جمعیت کشور را تشکیل میدادند. 1

Consequently, standards fell, and educational institutions began to turn out graduates who were even less qualified than their predecessors used to be. All this is not to mention the problems arising from the typical overconcentration of the education bureaucracy, with the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Teheran grotesquely involved in the problems of educational institutes in distant places; or the pressures brought by the SAVAK on university staff to show administrative and academic leniency to the students, in the hope of preventing political discontent. 15 According to a sample survey conducted by the Ministry of Science, and published in June 1973, 48 per cent of the (responding) students in universities and colleges of higher education came from bureaucratic families, 35 per cent from the industrial and commercial classes, 7 per cent from the families of landlords and independent farmers, 2 per cent from the urban working class, and 1 per cent from the peasantry. 16 It will be useful to add that in 1973 the last

two classes made up around 85 per cent of the country's population.Mohammad Ali Katoozian

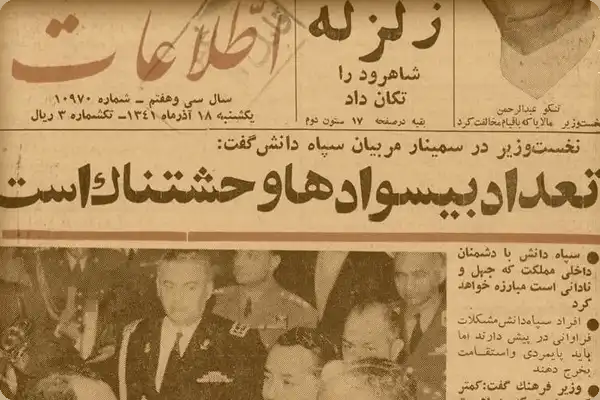

نرخ باسوادی در ایران

محمدعلی [همایون] کاتوزیان، عضو دانشکده مطالعات شرقی دانشگاه آکسفورد، در کتاب «اقتصاد سیاسی ایران مدرن: استبداد و شبه مدرنیسم» مینویسد:

در زمانی که درصد قابل ملاحظهای از جمعیت کشور بیسواد بود، بخش قابل توجهی از بودجه آموزشی صرف شبکههای آموزشی پر هزینه شد. تا سال 1978م [1357 شمسی] و علیرغم وجود سپاه دانش، تنها 65/5 درصد گروه سنی شش تا بیست و نه ساله میتوانستند بخوانند و بنویسند: از میان شهریان 81/9 درصد و از میان روستاییان فقط 48 درصد در این گروه جای داشتند. بر پایه این آمار و ارقام و دیگر آمار رسمی باید نتیجه گرفت که حدود 65 درصد از کل جمعیت و 80 درصد از جمعیت روستایی (بالای شش سال) احتمالاً هنوز بیسواد هستند. 2

at a time when the country lacked a basic standard of literacy and numeracy. Notwithstanding the Literacy Corps, by 1978 only 65.6 per cent of the age specific population between six and twenty-nine years old could read and write: this was made up of 81.9 per cent of the urban, and only 48.0 per cent of the rural, population in that age group. It follows that, on the basis of these and other offical figures, about 65 per cent of the total population and 80 per cent of the rural population (above the age of six), must still be illiterate.

Mohammad Ali Katoozian

فرد هالیدی، نویسنده و متخصص روابط بینالملل و خاورمیانه، در کتاب «ایران: دیکتاتوری و توسعه» مینویسد:

هنوز اکثریت جمعیت ایران بیسوادند؛ طبق برآورد رسمی سال ۱۹۷۲م [۱۳۵۱ شمسی] نسبت بیسوادان ۶۲ درصد بود، اما رقم واقعی به طور قطع بیش از این بود.3

The majority of the Iranian population are, in the first place, still illiterate; the official estimate was 62 per cent in 1976 but the real figure was almost certainly higher.

Fred Holliday

سواد و کارآیی نیروی انسانی

فرد هالیدی، نویسنده و متخصص روابط بینالملل و خاورمیانه، در کتاب «ایران: دیکتاتوری و توسعه» مینویسد:

ایران دارای یک سیستم آموزش و پرورش است که به نحو تأسفآوری در برآوردن نیازهای صنعتی شدن کشور ناتوان است: در اواخر سالهای ۱۹۵۰م [1329 شمسی] تعداد کسانی که دانشگاه را تمام میکردند در ایران برابر تعداد دانشآموختگان یکصد سال پیش ژاپن بود و با افزایش تعداد نفرات کیفیت تحصیلات عالی پائین آمده است. هنوز ایران از ۶۰ درصد بیسوادی یعنی نسبتی بالاتر از نسبت بیسوادی در هندوستان رنج میبرد و این امر نیز در کارآیی کلی نیروی کار تأثیر عمدهای دارد؛ ولو اینکه این تأثیر را نتوان اندازه گرفت.4

Moreover, Iran has an educa- tional system that is woefully inadequate to the needs of an industrializing nation: in the late 1950s it was producing only as many university graduates as Japan a century before and as the output of higher education has increased so the quality has fallen. Lower down the scale Iran still suffers from illiteracy of over 60 per cent higher than India and this too must have a major if unmeasurable effect on the overall efficiency of the workforce.

Fred Holliday

کیفیت آموزشی مدارس و دانشگاهها

سینتیا هلمز، پژوهشگر آمریکایی و همسر ریچارد هلمز رئیس اسبق سیا و سفیر آمریکا در ایران در پنج سال آخر رژیم پهلوی، در کتاب «خاطرات یک همسر سفیر در ایران» مینویسد:

تا اواسط دهه ۱۹۷۰م [۱۳۵۰ شمسی] هشت دانشگاه تأسیس شده بود و ایجاد تعدادی دیگر، نظیر یک دانشگاه براساس روش فرانسوی و یکی براساس روش آلمانی در دست بررسی بود. تمامی رشتههای تحصیلی در دانشگاه پهلوی شیراز به انگلیسی تدریس میگردید.

متأسفانه رشد کمّی تحصیلات بیش از رشد کیفی آن بود. شاه به این معنی توجه داشت و خیلی رک و راست درباره ارزش مدارک دانشگاهی سخن گفته و آنها را دانشنامه جهالت مینامید. بین سالهای ۷۵-۱۹۷۴م [۵۴-۱۳۵۳ شمسی]، هنگامی که بیش از نصف جمعیت ایران زیر هفده سال بودند، مجموع آموزگاران و دبیران مدارس ابتدایی و متوسطه به صد و هشتاد هزار نفر میرسید. فقط پنج درصد از معلمین دوره ابتدایی را به پایان رسانده بودند و تنها حدود ده درصد از دانشگاه فارغالتحصیل شده بودند.5

By the mid-1970s there were eight universities and more in the planning stage, and of the latter one was to be French oriented and one German. All courses at Pahlavi University in Shiraz were conducted in English.

Unfortunately, the quantity of education improved more than the quality. The Shah recognized this and was surprisingly outspoken about the caliber of the university degrees, calling them "degrees of ignorance." Between 1974-75, when more than half the population of Iran was under seventeen years old, the total number of teachers in primary and secondary schools was about one hundred eighty thousand. Five percent of the teachers had completed primary school only, and about ten percent had graduated from college.Cynthia Holmes

منابع:

- 1. Homa katouzian, The Political Economy of Modern Iran: Despotism and Pseudo-Modernism, 1926–1979, p289

- 2. Homa katouzian, The Political Economy of Modern Iran: Despotism and Pseudo-Modernism, 1926–1979, p288

- 3. Fred E. Halliday, Iran: Dictatorship and Development, p182

- 4. Fred E. Halliday, Iran: Dictatorship and Development, p163

- 5. Cynthia Helms, An ambassador’s wife in Iran, p162